On its surface, words are not numbers. But words have similarities, differences, associations, relations and connections. For example, ‘‘man’’ and ‘‘woman’’ are words that describe humans, while ‘‘apple’’ and ‘‘watermelon’’ are fruit names. The flow of words in an article always follow certain rules. How to quantify a word so as to reflex its relationship with other words, as well as its statistics in training text data? In this post, we’ll look at word embeddings, i.e. mapping of words in dictionary to multidimensional real vectors. We discuss two specific embedding methods, TF-IDF and word2vec. After words are embedded into a vector space, it is then possible to apply neural network models to them to output probabilities on words.

Word embedding is the first step in most applications of NLP, like text analysis, text mining, machine translation and so on. For example, since a document is consisted of words, once we have word vectors, we can also represent a document by a vector in some way, for example by averaging over all word vectors in the document. Then we can compare similarity between two documents by $\cos(d_1,d_2)$. This is useful for applications like information retrieval, plagiarism detection, and news recommendation system.

TF-IDF

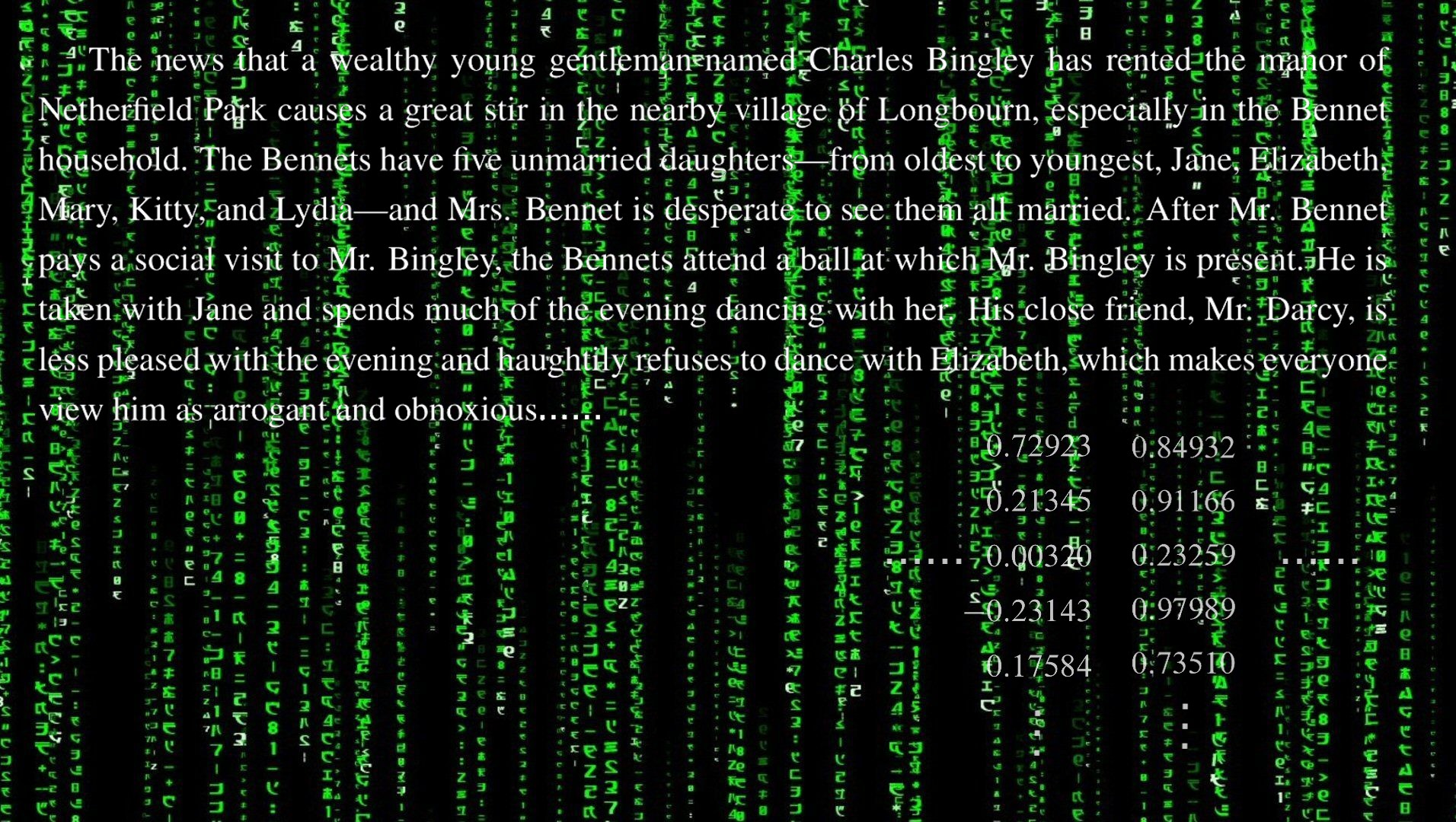

How to map or assign each word with a vector in some vector space? This entirely depends on our goal. One comes from information retrieval, where dimensions are documents $D$, and numerical value in each dimension $d$ of a word $w$ represents relevance/importance of that word $w$ to the document $d$. The list of word vectors (Table 1) is called a term-document matrix. We mention that dimensions can also be words themselves, where numerical value $(w_1, w_j)$ can represent number of times $w_j$ appears in a $\pm4$ window around $w_1$ in some training corpus.

Table 1: term-document matrix

Table 1: term-document matrix

Once we mapped each word with a vector, the most basic way to measure similarity between two words $v$ and $w$ is to use cosine

\[\cos(v, w) = \frac{v\cdot w}{\|v\|\|w\|}.\]Let’s now think about information retrieval. Given a query $q=(w_1,\ldots,w_n)$, we need to rank the collection of documents $D$. The most straightforward way is to assign each document $d$ a value for $w_1$, a value for $w_2$, and so on, and add them up, to get a final value for $d$. Then ank documents in $D$ according to the outputs of this (linear) ranking function.

How to assign a value to $(w,d)$ to represent relevance of word $w$ to document $d$? i.e., how to assign entry values in Table 1? The most straightforward approach is to count the number of times that $w$ appears in $d$:

\[\mathrm{tf}_{w,d} = \mathrm{count}(w,d).\]Besides counting, there are other calculations (Table 2). Among them, the most common practice is to take $\log_{10}$ of the raw count

\[\mathrm{tf}_{w,d} = \log_{10}(\mathrm{count}(w,d)+1).\] Table 2: Variants of tf terms

Table 2: Variants of tf terms

Next, in the TF-IDF method, the TF term $\mathrm{tf}_{w,d}$ is weighted by the inverse document frequency of the word $w$ across a set of documents $D$. This means how common or rare a word is in the entire document set. The closer it is to $0$, the more common a word is. This metric can be calculated by taking the total number of documents, dividing it by the number of documents that contain a word, and calculating the logarithm:

\[\mathrm{idf}_{w} = \log_{10}\left(\frac{N}{\mathrm{df}_{w}}\right).\]So, if a word is very common and appears in many documents, e.g. for words like ‘‘the’’, ‘‘and’’, or ‘‘this’’, this number will approach $0$. Otherwise, it will approach infinity.

Multiplying these two numbers results in the TF-IDF score of a word in a document

\[(w,d) = \mathrm{tf}_{w,d} \cdot \mathrm{idf}_{w}\]The higher the score, the more relevant that word is in that particular document.

To summerize, TF-IDF is basically word count in a document, adjusted by some functions and document frequencies.

word2vec

From the viewpoint of embedding, the TF-IDF method produces sparse vectors (Table 1), with most entries being zero. In contrast, the word2vec method [1] produces dense word vectors, typically of dimension $50\sim1000$. Actually we are referring to “skip-gram with negative sampling” in the word2vec software package, but it is often loosely referred to as word2vec.

First randomly initialize some word as a vector $w\in\mathbb{R}^d$. Define a binary classification task as follows: given $w\in\mathbb{R}^d$, predict if $c\in\mathbb{R}^d$ is a context word, i.e. if it should generally appear near $w$ in text data. Define the probability of being positive as

\[\mathbb{P}(+\mid w, c) = \sigma(w\cdot c) = \frac{1}{1+\exp(-w\cdot c)}.\](The probability of being negative is then

\(\mathbb{P}(-\mid w, c) = 1- \sigma(w\cdot c) = \frac{\exp(-w\cdot c)}{1+\exp(-w\cdot c)}.\) )

For context $c_{1:L}$, the model makes the assumption that all context words are independent, so the probability is

\[\mathbb{P}(+\mid w, c_{1:L}) = \prod_{i=1}^L\sigma(w\cdot c_i).\] \[\log\mathbb{P}(+\mid w, c_{1:L}) = \sum_{i=1}^L\log\sigma(w\cdot c_i).\]For each word $w$, every nearby word within e.g. $L=\pm2$ window in the training data is a positive context. An example is as follows:

For every positive sample $(w,c)$, we generate $k$ noise samples $(w,n_1),\cdots,(w,n_k)$ as negative samples by randomly sampling the lexicon. In practice, it is common to use not the plain word frequencies, but

\[\mathbb{P}_{\alpha}(w) = \frac{\mathrm{count}(w)^\alpha}{\sum_{w'}\mathrm{count}(w')^\alpha}\]as the probabilities, with $\alpha=0.75$, to give less frequent words higher probabilities.

Then, we can train the logistic regression model to classify positive samples and negative samples. For each sample pair \(\{(w,c),(w,n_1),\ldots,(w,n_k)\}\), the negative log-likelihood loss is

\[\begin{split} L &= -\log\left[\mathbb{P}(+\mid w,c)\prod_{i=1}^k\mathbb{P}(-\mid w,n_i)\right]\\ &= -\left[\log\sigma(w\cdot c) + \sum_{i=1}^k\log[1-\sigma(w\cdot n_i)]\right]. \end{split}\]The word2vec embedding method is an example of Noise Contrastive Estimation. When we need to learn parameters of a non-discriminative model for which we do not have an easy objective, we can convert the problem to a binary classification task and let the model learn to distinguish between positive training samples and noises. Here, a positive sample $(w,c)$ simply consists of a word $w$ and a surrounding word $c$. The weight $w\in\mathbb{R}^d$ is learned so that it is similar (i.e. has a large dot product value) to its surroundings in the training corpus.

Note that, in the end, for each word, two set of parameters are learned because a word can be either a word for which we want to have an embedding, and a context or noise for other words. Thus if we denote the vocabulary set as $V$, then the output of the algorithm is a matrix of $2\vert V\vert$ vectors, each of dimension $d$, formed by concatenating the target embedding $W$ and the context $+$ noise embedding $C$. It is common to add them together, representing word $i$ with the vector $w_i+c_i$. Alternatively we can throw away the $C$ matrix and just represent each word $i$ by the vector $w_i$.

Neural language models

Once we have word embeddings, we can use them as inputs to neural networks models, for modeling probabilities on words and sentences. Embeddings should produce better generalization than primitive models like $n$-gram models. For example, suppose in the training data we have the sentence

“…make sure that the electric car gets charged”,

and our test set has

“…make sure that the electric vehicle gets [ ]”.

Suppose the word “vehicle” is in the training set for the embedding, but there is no ‘‘vehicle gets….’’. An $n$-gram model would be unable to infer a reasonable prediction from the training data. But a neural language model, knowing that ‘‘car’’ and ‘‘vehicle’’ have similar embeddings, should be able to generalize from the ‘‘car’’ context to assign a high enough probability to ‘‘charged’’ following ‘‘vehicle’’.

Embeddings can also be learned during training. We can initialize $\vert V\vert$ embeddings, each of dimension $d$, and directly feed them into a neural network, without using embeddings pretrained by e.g. word2vec. In other words, we can encode each word as a one-hot vector $x$ of size $\vert V\vert\times1$, with value $1$ in some index and $0$ otherwise, and initialize a random $d\times\vert V\vert$ matrix $E$ as the embedding matrix. The product $Ex$ then selects the embedding for word $x$. The language model becomes

\[\begin{align*} e &= (Ex_1,Ex_2,\ldots,Ex_{|V|}),\\ h &= \sigma(We + b),\\ z &= Uh,\\ \hat{y} &= \mathrm{softmax}(z). \end{align*}\]See Figure 1. The model is initialized with random weights. Training proceeds by concatenating all the sentences to a very long text and then iteratively moving through the text predicting each word $w_t$. The neural language model was first proposed by Bengio et al. [2].

Figure 1: Neural language model

Figure 1: Neural language model

Summary

By embedding words into real vector spaces in a way that reflects their relations in training corpus, we are able to utilize model continuity for better generalization over $n$-gram models: a small input variation should yield a small output variation. word2vec is one such method, where a word vector is learned by distinguishing between its surrounding contexts and random noises. On the other hand, we can see from the figure above that the language model is data hungry: a large amount of training data is needed to cover all words and all possible contexts. If a word never appears in the training corpus, its embedding would not be learned. The model is still very “coarse”, and processes limited capacity such that problems like long term dependency are not addressed.

Cite as:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

@article{lifei2022embedding,

title = "Embeddings and the word2vec Method",

author = "Li, Fei",

journal = "https://lifeitech.github.io",

year = "2022",

url = "https://lifeitech.github.io/posts/embedding-and-word2vec/"

}

References

[1] Mikolov, Tomas, et al. “Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.3781 (2013).

[2] Bengio, Yoshua, Réjean Ducharme, and Pascal Vincent. “A neural probabilistic language model.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 13 (2000).

Comments powered by Disqus.