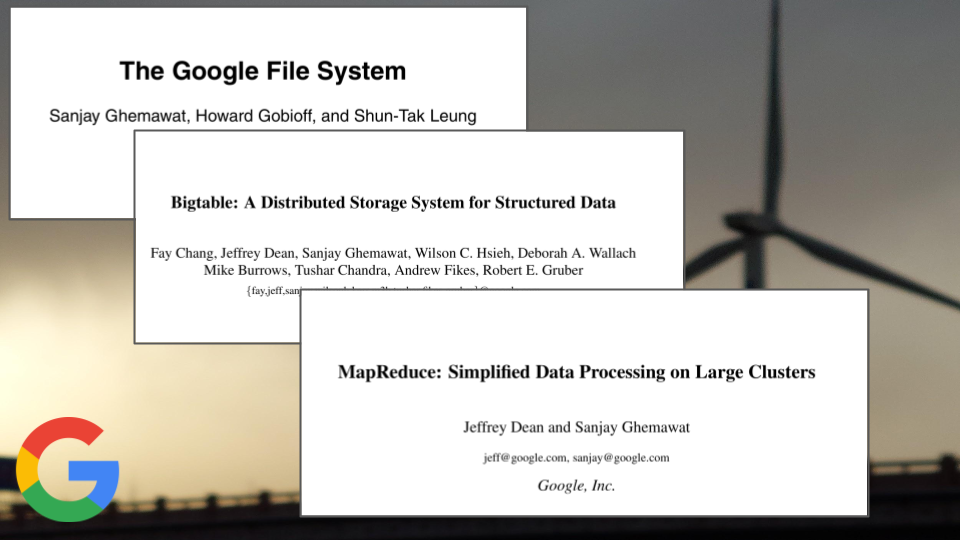

Have you wondered about the inner workings of big data? How parallel and distributed computing work? In this post we will have a look at Google’s three early works in the 2000s that are the basis of Apache Hadoop: the Google File System (GFS), Bigtable and MapReduce.

As the Internet rapidly developed in the late 90s, it soon became impractical for many enterprises to store and analyze all of their data on a single machine. Naturally, distributed data storage and processing techniques arose. With gigabytes of data continuously being generated, the only way to store them is to make use of clusters of computers. The task of data storage has to be distributed across many machines, and big data techniques concern how to coordinate those machines to achieve efficiency, reliability, and ease of use. Today, the Hadoop ecosystem encompasses many popular big data technologies, including HDFS (Hadoop Distributed File System), Hive, Pig, YARN, MapReduce, Spark, HBase, Cassandra, Kafka, Storm, and others. Those projects were initially inspired by Google’s Google File System (GFS) (Ghemawat et al., 2003), Bigtable (Chang et al., 2008) and MapReduce (Dean & Ghemawat, 2008), and were meant to be open source replacements for Google’s commercial technologies. So to understand how those technologies work, we will look at Google’s three big data technologies: the Google File System (GFS), MapReduce, and Google Bigtable.

The Google File System (GFS)

The Google File System (GFS) is a low level file system for distributed data storage. It provides a file system interface like on a single machine. GFS was designed under several principles, the most silient one is that component failures are norm rather than exception, so the system must be robust to all kinds of failures and deliver correct outcomes even in the presence of component failures.

A GFS consists of a single master and several chunkservers, and is accessed by multiple clients. All of them are just ordinary Linux machines. Files are divided into fixed-size (64MB) chunks. Each chunk is replicated on 3 chunkservers for reliability.

For a client to request data, it first contacts the master, and the master tells the client the chunkserver that has the data, and the client then contacts the chunkserver, and the chunkserver sends data to the client. See the figure below for GFS architecture. In the GFS architecture, there is only a single master, but the master state is replicated for reliability. Note that clients never read and write files through the master, since under that situation the master will become a bottleneck.

Google File System (GFS): read data

Google File System (GFS): read data

The system also keeps an operation log that contains a historical record of important metadata changes. This log is also replicated on multiple machines.

To write data, the client first contacts the master about the chunk location that it wants to modify. The master replies with the location of three chunkservers that host the chunk. One replica is designated to be primary. After knowing the three chunkservers, the client sends the data to the server that is closest to it. Then the data are shared within the three servers. After the data has been cached by all three servers, the writing process begins. The primary server writes to its own disk, and notifies other servers to do the same. When finished, the primary server notifies the client that they are done.

There are many other details of the system. For a complete description please refer to (Ghemawat et al., 2003).

Google Bigtable

Bigtable is a distributed (NoSQL) database. While the Google File System is concerned about how to store files that are too large and too many, Bigtable has a higher level concern about how to efficiently store and retrieve actual data points, just like what other database systems are concerned about. Examples are personnel information, product information, properties of webpages, and so on.

A Bigtable is a list of sorted <key, value> pairs. To store a large Bigtable, we divide it into many small tables called tablets, and we store information about those tablets into a metadata tablet. We further divide tablets into SSTables (“S” for “small”).

So, a tablet contains a list of SSTables and their addresses, and it is each SSTable that stores actual data (key-value pairs). SSTable files are stored in GFS.

Google Bigtable

Google Bigtable

Write data

How to insert a key-value pair <k, v> into Bigtable? Because SSTables reside in hard disk, writing into SSTables directly would be slow, not to mention that we have to sort the SSTable once we inserted the data. Thus, we establish a table called memTable in memory, and we write the data into memTable. When it is full, we save the table on disk, so that it becomes another SSTable.

Bigtable Write

Bigtable Write

To prevent loss of memTable in memory, we maintain a tablet log on hard disk, and write every step to the log before writing to memTable.

Bigtable Tablet Log

Bigtable Tablet Log

Read data

We index each SSTable on hard disk, and load the index into memory when the SSTable is opened. To lookup an SSTable, we can perform a binary search in the in-memory index, and then read the table from disk.

To read the value for a key k, the operation is executed on a merged view of the sequence of SSTables and the memTable. Since the SSTables and the memTable are lexicographically sorted data structures, the merged view can be formed efficiently.

Bloom filters

A read operation has to read from all SSTables that make up the state of a tablet. If these SSTables are not in memory, we may end up doing many disk accesses. We can further accelerate read operation by using Bloom filters.

Bloom filters are useful for testing whether an element is in a set. A Bloom filter is an array of binary bits (0 or 1) together with some hash functions. A hash function maps its input to some position of the array. To add an element, set the value to 1 for all output positions of all the hash functions.

If an element is in the set, then all hash functions must map it to 1 because that is how we added it, but if an element is not present, then it is not very likely that all hash outputs happen to correspond to 1. If at least one output is 0, then for sure it is not in the set. On the other hand, there is a small possibility of being false positive.

For Bloom filters, the running time for checking an element is proportional to the number of hash functions, but is independent of the size of the set, so it can be fast for large sets.

Bloom filter: a key is added by setting 1 for all hash mappings. To check if a key is present, check whether all hash functions return 1

Bloom filter: a key is added by setting 1 for all hash mappings. To check if a key is present, check whether all hash functions return 1

Bloom filter: if one hash function maps an input to 0, then the input is not in the set.

Bloom filter: if one hash function maps an input to 0, then the input is not in the set.

A bloom filter is added for each SSTable. The final design looks like this:

Bigtable read operation

Bigtable read operation

To query the value for a key, we first input the key to each Bloom filter of each SSTable. If a result is negative, then for sure the key is not in that SSTable, so we don’t have to bother searching in that SSTable. We just need to search in SSTables where the result is positive. This can drastically reduces the number of disk seeks required for read operations.

Logic views

The logic view of a Bigtable has rows and columns. A row represents an entity, for example a website. Columns contain various properties of the entity. Some columns are grouped together, called a “column family”. Each cell can contain multiple versions of the same data, indexed by timestamps.

Bigtable logic view

Bigtable logic view

To map from the logic view to physical view, (row, column, time) tuples are used as keys that map to corresponding cell values.

Bigtable mapping from logic view to physical view

Bigtable mapping from logic view to physical view

MapReduce

After we solved the problem of how to distributedly store data, now it is time to consider how to do distributed computation over the data. The idea of MapReduce (Dean & Ghemawat, 2008) is to decompose the data, and recombine. There are six steps: input, split, map, shuffle, reduce and output. A good analogy is the process of making Subway sandwiches. The data are like many kind of breads, vegetables and meat and other ingredients. We distribute them to different chefs. Some person gets some tomatoes while another gets some onions (split). Then each chef cuts his ingredients at hands into pieces (map). Ingredients are then grouped together into boxes (shuffle). When a customer orders a sandwich, the staff would pick up bread, meat and vegetables preferred by the customer from various boxes and put them together to make a sandwich (reduce) and finally serves it to the customer.

Let’s see how MapReduce is useful for Google’s search engine. Suppose we have tons of articles (webpages) stored across thousands of machines. Let’s see how to calculate word frequencies, as well as how to establish an inverted index of the articles.

Word frequencies

The split process distributes articles to different workers. Then each worker goes through a for loop and counts each word in the article assigned to him as 1 in the map process. In the shuffle process, we put the same word across different workers into a single box. In reduce, we just need to sum up the 1s in each box together, or in other words count the size of each box. Finally, we output word frequencies as a list of values indexed by words. The figure below illustrates the MapReduce process. To our sandwich analogy, the final output is like a sandwich, where each value is the amount of the ingredient.

MapReduce example: count word frequencies in articles

MapReduce example: count word frequencies in articles

Inverted index

An inverted index is a list indexed by words, where the value for each word is a list of documents id that contain the word. This allows us to quickly find which documents contain a particular input keyword, which is very useful for search engines.

The process for establishing an inverted index is similar to counting word frequencies. The output value for each word is a list, instead of an integer.

MapReduce example: inverted index

MapReduce example: inverted index

Summary

In this post, we learned Google’s three technologies that are of crucial importance in today’s big data era: Google File System, Bigtable and MapReduce. They are the pioneers of modern big data technologies. Their common purpose is to process data that reside over thousands of machines. The Google File System is concerned about lower level data storage. It divides machines into master and chunkservers. The master keeps information about chunkservers and coordinates read and write operations. Files are replicated over multiple chunkservers. Bigtable stores a table by mapping its entries to key-value pairs. It utilizes memory for speed, and hard disk replication for reliability. To perform computation over such large amount of data, the MapReduce paradigm takes a divide and conquer approach. It divides the problem into many smaller problems. After smaller problems are solved independently by distributed workers, their results are combined for final answer.

Cite as:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

@article{lifei2022googlebigdata,

title = "Google's three big data technologies: GFS, Bigtable and MapReduce",

author = "Li, Fei",

journal = "https://lifeitech.github.io",

year = "2022",

url = "https://lifeitech.github.io/posts/google-big-data/"

}

References

- Ghemawat, S., Gobioff, H., & Leung, S.-T. (2003). The Google file system. Proceedings of the Nineteenth ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, 29–43.

- Chang, F., Dean, J., Ghemawat, S., Hsieh, W. C., Wallach, D. A., Burrows, M., Chandra, T., Fikes, A., & Gruber, R. E. (2008). Bigtable: A distributed storage system for structured data. ACM Transactions on Computer Systems (TOCS), 26(2), 1–26.

- Dean, J., & Ghemawat, S. (2008). MapReduce: simplified data processing on large clusters. Communications of the ACM, 51(1), 107–113.

Comments powered by Disqus.